AP U.S. History Notes: Period 3

April 10, 2024

Take your AP studies to the next level with Barron’s AP U.S. History Period 3 notes. Review essential vocabulary, key exam topics, and a timeline of what happens in period 3 of APUSH. Looking for more APUSH study resources? Check out Barron’s AP U.S. History Premium Test Prep Book and our AP U.S. History Podcast.

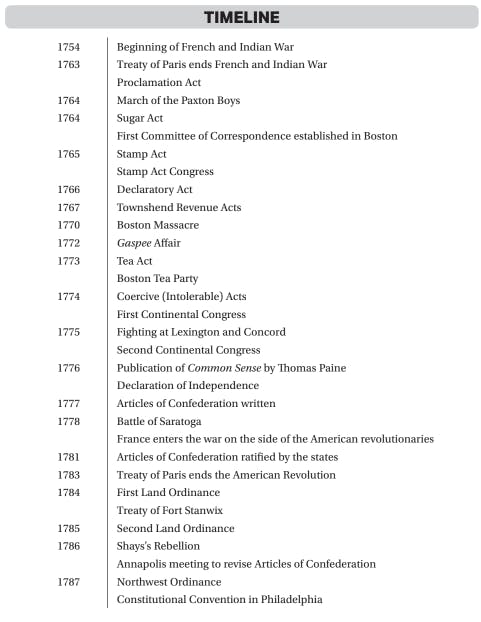

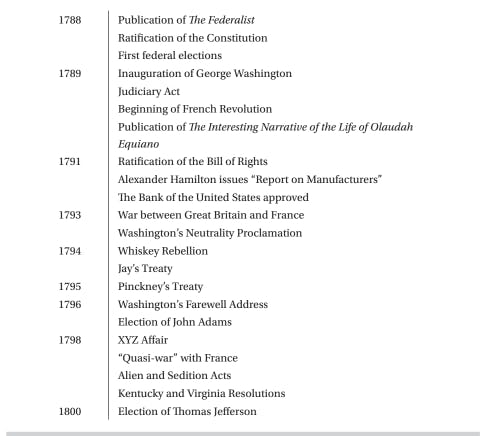

AP U.S. History Notes: Period 3 Timeline

This graphic gives a brief timeline of key events that took place during AP U.S. History Period 3.

AP U.S. History Notes: Period 3 Overview

The third period covered on the AP U.S. history exam took place between the years 1754-1800 and is referred to as “The Crisis of Empire, Revolution, and Nation Building.” The attempt by Great Britain to restructure its North American empire following the French and Indian War and to assert greater control over its colonies led to intense colonial resistance and finally to revolution. The American Revolution produced a new American republic. The first decades of the United States were marked by a struggle over the new nation’s social, political, and economic identity.

11 Things to Know About AP U.S. History Period 3

1. Competition among the British, French, and American Indian nations culminated in the French and Indian War (1754–1763). American Indians were forced to adjust alliances in the wake of the victory of Great Britain over France. The war proved to be a turning point in relations between Great Britain and the thirteen colonies. Before the war, the British unofficial policy of “salutary neglect” allowed both Great Britain and the colonies to benefit under loosely enforced mercantilist rules. After the war, the British government enacted a series of measures designed to assert greater control over its North American colonies.

2. In the aftermath of the French and Indian War (1754–1763), new taxes enacted by the British and more rigorous enforcement of existing taxes generated intense resentment and resistance among many colonists. This movement culminated in the independence movement and revolution against Great Britain.

3. The American Revolution occurred in the midst of a fertile period in the history of ideas. A variety of schools of thought put forth contending new ideas about society, politics, religion, and governance. Many colonists came to believe in the superiority of republican forms of government. This was evident in key documents from the period of the American Revolution, including Thomas Paine’s Common Sense (1776) and the Declaration of Independence (1776).

4. At the onset of the American Revolution, the Patriot cause faced serious obstacles, including considerable Loyalist opposition and the overwhelming military might of Great Britain. Despite these factors, the rebellious colonists were successful. The military leadership of George Washington, the actions of colonial militias and the Continental Army, the ideological commitment of many colonists, and support from foreign powers all worked to the advantage of the Patriot cause.

5. The American Revolution generated debates in the United States about what type of society would emerge in the new nation. An ongoing tension emerged between those who sought to expand democratic participation and those who sought to maintain traditional forms of inequality. In addition, the ideas of the American Revolution were invoked by movements for change in other countries in the decades following the birth of the United States.

6. After declaring independence, Americans experimented with different forms of government, both on the state level and the national level. The Articles of Confederation established a weak central government, with the states retaining a great deal of their powers. The weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation soon became apparent as the United States faced a series of domestic and international challenges.

7. As the limitations of the Articles of Confederation became more apparent, American political leaders drafted the Constitution, which was designed to strengthen the central government. Debates over the Constitution led to the adoption of a Bill of Rights as Americans continued to debate the proper balance between liberty and order.

8. The delegates at the Constitutional Convention created a national government that was more powerful than the one that had existed under the Articles of Confederation. However, the structure of the Constitution contained safeguards against the government assuming excessive powers. Three branches were created, each with the power to check the power of the other two. A system of federalism was also created, allowing state governments to retain certain powers.

9. The United States faced a host of challenges in its first years of independence. The continued presence of European powers in North America challenged the government to find ways to safeguard the borders. At the same time, war and conflict in Europe made it difficult for the United States to pursue both free trade and neutrality. In addition, neither the Constitution nor political leaders in the early national period clarified the status of American Indians in the United States, setting the stage for future conflicts. Finally, the nation experienced heated debates over a national bank, the future economic direction of the United States, and the proper balance between security and civil liberties.

10. The period from independence to the end of the eighteenth century witnessed the development of cultural forms that united the new country and helped it establish an identity separate from its European roots.

11. The closing decades of the eighteenth century witnessed increased migrations of white settlers into the interior of North America. These migrations led to conflicts between settlers and American Indians, tensions between backcountry farmers and coastal elites, and new forms of cultural blending. As Americans moved deeper into the interior, attitudes about slavery became more entrenched.

AP U.S. History Notes: Key Topics in Period 3

The Seven Years’ War (The French and Indian War)

- The French and Indian War: In the 1740s and 1750s, British colonists began to venture from Virginia to settle beyond the Appalachian Mountains in the Ohio River Valley—land claimed by France. At the time, France was increasing its presence in the Ohio River area in order to build up the fur trade. France began building fortifications in the region, notably Fort Duquesne at present-day Pittsburgh. The British colonists built a makeshift fort of their own nearby, Fort Necessity. In 1754, skirmishes between the two groups led to the beginning of the French and Indian War, which brought on a shift in American Indian alliances.

- The Treaty of Paris: In the Treaty of Paris, France surrendered virtually its entire North American empire. It ceded to Great Britain all French territory in Canada and east of the Mississippi River. France ceded to Spain all of its territory west of the Mississippi River.

- The Stamp Act: The Stamp Act (1765) provoked the most intense colonial opposition of all measures enacted by the British following the French and Indian War. It represented a departure from previous British colonial policy. Previous tax acts were aimed at regulating trade; this act was purely designed to raise revenue. It was a direct tax on the colonists rather than an indirect trade duty. The act imposed a tax on all sorts of printed matter in the colonies—court documents, books, almanacs, and deeds.

- Pontiac’s Rebellion: The Ottawa chief, Pontiac, and other Indian leaders organized resistance to British troops stationed around the Great Lakes and southward on several rivers.

- Proclamation of 1763: In response to the outbreak of Pontiac’s Rebellion, Great Britain issued the Proclamation of 1763, which drew a line through the Appalachian Mountains. Great Britain ordered the colonists not to settle beyond the line.

- Paxton Boys: As tensions between American Indians and settlers increased, a vigilante group of Scots-Irish immigrants, called the Paxton Boys, organized raids against American Indians on the Pennsylvania frontier. In 1763, these raids included an attack on peaceful Conestoga Indians (many of them Christians) that resulted in 20 deaths.

Taxation Without Representation

- Declarations of the Stamp Act Congress: In October 1765, delegates from nine colonies met in New York and drew up a document listing grievances, which went beyond the Stamp Act itself. The Declarations of the Stamp Act Congress asserted that only representatives elected by colonists could enact taxes on the colonies.

- The Boston Massacre: During the winter of 1770 a deadly incident between British soldiers and a group of Bostonians reverberated throughout the colonies. The Boston Massacre (1770), as the incident came to be known, occurred in March as a disagreement between an on-duty British sentry and a young wigmaker’s apprentice escalated into a scuffle. Angry colonists heckled and threw stones at British sentries ordered out to restore calm. Finally, the troops fired on the colonists, resulting in five deaths.

- The Tea Act: The British East India Company was in crisis; its stock value had virtually collapsed. To bolster the company, the British passed the Tea Act, which greatly reduced taxes on tea sold in the colonies by the British East India Company. The act enabled the company to sell massive quantities of low-priced tea directly to colonial merchants on consignment, thus bypassing local middlemen and undercutting smugglers. This act actually lowered tea prices in Boston, but it angered many colonists who accused the British of doing special favors for a large company.

- The Coercive/Intolerable Acts: The British passed a series of acts in 1774, in the wake of the Boston Tea Party, called the Coercive Acts, or Intolerable Acts. British authorities hoped that the Coercive Acts would make an example of Massachusetts and isolate it from the other British colonies. The opposite occurred. Colonists throughout colonial America resented the British for these acts.

- First Continental Congress: The First Continental Congress met in Philadelphia in September and October 1774, with representatives from each of the thirteen colonies, except Georgia. The Congress passed several resolutions including nonimportation, nonexportation, and non-consumption agreements in an attempt to cut off all trade with Britain.

Philosophical Foundations of the American Revolution

- Protestant Evangelicalism: A more intense and radical form of Protestantism which began in the 1700s and was more focused on individual conversion and less centered on established churches.

- John Locke: Perhaps the most influential Enlightenment thinker, read widely in America during the time of the Revolution. Locke argued that a ruler gains legitimacy through the consent of the governed. The basic responsibility of government is to protect the natural rights of the people; Locke identified the most basic of these rights as life, liberty, and property. If a government should fail to protect these basic rights, it is the right of the citizens to overthrow that government. Locke’s theory of natural rights states that power to govern belongs to the people.

- Olive Branch Petition: Congress sent the “Olive Branch Petition” to King George III in July 1775, affirming loyalty to the British King and blaming the current problems on Parliament. The petition proposed a structure in which the colonies would exercise greater autonomy within the British empire, and the British would enact more equitable trade and tax regulations. George rejected the Olive Branch Petition without reading it.

- Common Sense: As the debate over independence ensued, Thomas Paine published a best-selling pamphlet called Common Sense. He advocated that the American colonies declare independence from Great Britain. He wrote that he could not see a “single advantage” in “being connected with Great Britain.”

- Declaration of Independence: On July 4, 1776, the delegates to the Second Continental Congress formally ratified the Declaration of Independence. The first draft of the document was written by Thomas Jefferson in consultation with fellow members of a five-person committee appointed by Congress; the draft subsequently underwent edits by the entire Second Continental Congress. The body of the Declaration of Independence is a list of grievances against the king of Great Britain, but the eloquent preamble contains key elements of Locke’s natural rights theory.

The American Revolution

- “The Shot Heard Round the World:” In April 1775, fighting began between colonists and British troops in the Massachusetts towns of Lexington and Concord. Americans often call the first shot of this clash “the shot heard round the world.” The event symbolized a marked shift in the colonial situation from resistance to rebellion.

- The First Phase of the American Revolutionary War: The first phase (1775–1776) took place primarily in New England. In this phase, Great Britain did not grasp the depth of Patriot sentiment among many colonists. The British thought that the conflict was essentially brought on by an impetuous minority in New England. After the British suffered heavy losses in their victory at the Battle of Bunker Hill (March 1776), they abandoned Boston and reevaluated their strategy.

- The Second Phase of the American Revolutionary War: The second phase (1776–1778) occurred primarily in the middle colonies. The British thought that if they could maintain control of New York, they could isolate rebellious New England. A massive British force drove George Washington and his troops out of New York City in the summer of 1776. However, British forces coming south from Canada suffered a major defeat at the Battle of Saratoga in October 1777. Saratoga showed France that the colonists could mount formidable forces for battle. Early in 1778, France formally recognized the United States as an independent nation and agreed to supply military assistance.

- The Third Phase of the American Revolutionary War: The third phase (1778–1783) took place in the South. Great Britain hoped to rally loyalist sentiment in the South, where it was strongest, and even tap into resentment among the slave population there. The southern strategy did not bear fruit despite British victories at Savannah, Georgia, and Charleston, South Carolina. In the North, fighting had reached a stalemate, despite the aid that “turncoat” Benedict Arnold supplied to the British (1780). By October 1781, a joint American-French campaign caught British General Cornwallis off guard, and he surrendered at Yorktown, Virginia. Skirmishes continued between the two sides until the 1783 Treaty of Paris formally ended the American Revolution.

The Influence of Revolutionary Ideas

- “Natural Rights:” Despite the language of equality in the Declaration of Independence and in many state constitutions, political leaders were reluctant to apply such language to enslaved African Americans. In several northern states, slaves petitioned state legislatures to grant them their “natural rights,” namely freedom.

- Egalitarianism: The experience of women participating in the struggle for independence, from organizing boycotts to aiding men on the battlefield, gave rise to a sense of egalitarianism among many women and men.

- “Republican Motherhood:” The concept of “republican motherhood,” drawing together a number of elements, asserted that women did indeed have civic responsibilities in the evolving culture of the new nation. The concept drew on Enlightenment thinkers, such as John Locke, who asserted, in his Two Treatises on Government, that marriage should involve a greater degree of consent, challenging traditional notions of female subordination.

- The French Revolution: The first phase of the French Revolution was begun by the national legislature against the absolutist power of the monarch. The first phase had widespread support in the United States. Soon, the revolution entered a more radical phrase. In 1793, the monarchy was completely abolished, the power of the church was limited, and, during a fever of revolutionary zeal, more than 40,000 suspected enemies of the revolution were publicly executed, among them the king and queen of France.

The Articles of Confederation

- The Articles of Confederation: The Articles of Confederation were written in 1776, just as the Declaration of Independence was being written and debated. The Articles of Confederation, however, lack the philosophical grandeur of Thomas Jefferson’s document. The Articles essentially put down on paper what had come to exist organically over the previous year, as the First and Second Continental Congresses began to assume more powers and responsibilities. The main concern at the time was carrying out the war against Great Britain. The document was edited and sent to the states for ratification in 1777.

- Shays’s Rebellion: A farmers’ uprising in Massachusetts led by veteran Daniel Shays which is considered one of the important causes of the change in governing documents in the United States, from the Articles of Confederation to the Constitution. These farmers were responding to a perceived injustice as they had a decade earlier when under British rule. They closed down several courts and freed farmers from debtors’ prison. After several weeks, the governor and legislature took action, calling up nearly 4,000 armed men to suppress the rebellion. The insurrection reflected ongoing tensions between coastal elites and struggling farmers in the interior.

- Philadelphia Convention: By 1786, many Americans began to raise concerns about the stature of the United States on the world stage and the competency of a weak central government. With these concerns in mind, in 1786 a group of reformers received approval from Congress to meet in Annapolis, Maryland, to discuss possible changes in the Articles of Confederation. A follow-up meeting was scheduled in Philadelphia for May 1787. In between these meetings, Shays’s Rebellion erupted in Massachusetts. It was eventually put down, but it added fuel to the impetus to reform the governing structure. By the time of the Philadelphia meeting, the delegates were ready to scrap the entire Articles of Confederation and write something new.

The Constitutional Convention and Debates Over Ratification

- The Great Compromise: The delegates at the Constitutional Convention agreed that a central government with far greater powers was needed. After much wrangling, the delegates agreed on the Great Compromise, which created the basic structure of Congress as it now exists. The plan called for a House of Representatives, in which representation would be determined by the population of each state, and a Senate, in which each state would get two members.

- The Federalists: The supporters of the Constitution labeled themselves Federalists. Three important Federalist theorists were Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison.

- The Federalist: As the New York convention was debating ratification in late 1787 and 1788, the three wrote a series of articles that were later published in book form—The Federalist. This highly influential political tract outlined the failures of the Articles of Confederation and the benefits of a powerful government with checks and balances.

- Anti-Federalists: Opponents of the new Constitution, Anti-Federalists, as they were called by their Federalist adversaries, worried that the new government would be controlled by members of the elite. They saw the document as favoring the creation of a powerful, aristocratic ruling class. Leading Anti-Federalists were Patrick Henry and George Mason.

- The Bill of Rights: One of the first acts of Congress was passage of the Bill of Rights—the first ten amendments to the Constitution. Much of the language in the Bill of Rights, written by James Madison, comes from the various states’ constitutions.

The Constitution

- Legislative Branch: The powers of the legislative branch, Congress, are enumerated in Article I. These include the power to levy taxes, to regulate trade, to coin money, to establish post offices, to declare war, and to approve treaties. The framers of the Constitution wanted it to have the flexibility to deal with the needs of a changing society.

- Executive Branch: The powers of the executive branch, the president, are included in Article II. These include the power to suggest legislation, to command the armed forces, and to nominate judges. The president is charged with carrying out the laws of the land.

- Judiciary Branch: The powers of the judiciary, headed by the Supreme Court, are outlined in Article III. The federal judiciary has the power to hear cases involving people or entities from different states and to hear cases involving federal law.

- Federalism: Federalism refers to the evolving relationship between the national government and the states. The Constitution gave the national government considerably more power than had the Articles of Confederation. Under the Constitution, states still hold on to certain powers (reserved powers), but an expanded national government is given many new powers (delegated powers).

Shaping the New Republic

- Pinckney’s Treaty: Negotiations between the diplomats Thomas Pinckney of the United States and Don Manuel de Godoy of Spain resulted in Pinckney’s Treaty (1795; ratified in 1796). Spain agreed to allow for American shipping on the Mississippi River. The treaty also defined the border between the United States and Spanish-held territory in western Florida.

- The Judiciary Act of 1789: The Judiciary Act of 1789 created thirteen federal judicial districts. Each district had a district court as well as a circuit court that could hear appeals from the district courts. The Supreme Court could hear appeals from the circuit courts and would have the final say. In addition, the act stipulated that the Supreme Court could hear cases on appeal from state courts if the case involved federal law.

- “Unwritten Constitution:” President George Washington established several traditions and customs that have come to be known as the “unwritten constitution.” The establishment of a presidential cabinet is one of these customs.

- Neutrality Act: President Washington chose to remain neutral in the conflicts between Great Britain and France. He issued the Neutrality Act (1793) and he urged the United States to avoid permanent alliances with foreign powers. In his Farewell Address, he cautioned the newly independent nation against being drawn into the seemingly endless conflicts in Europe.

Developing an American Identity

- Noah Webster: Noah Webster, a noted author, political thinker, and educator, asserted that American culture was separate from, and superior to, British culture. He saw the United States as a tolerant, rational, democratic nation—distinct from the superstitions, ostentatious habits, and warring history of Europe. He published a three-volume set of textbooks that were intended for American school-children—A Grammatical Institute of the English Language.

- The Life of Washington: Mason Weems wrote a best-selling glowing biography of the nation’s first president, The Life of Washington, first published in 1800. A later edition of the book contained the imagined story of a young George Washington admitting to his father that he had damaged a cherry tree with his hatchet, prefacing the admission with the words, “I cannot tell a lie.”

- Charles Bullfinch: During this period, the first true architects appeared on the American scene. Among them was Charles Bulfinch (1763–1844) who is credited with bringing the Federal style to the United States after his European tour.

Movement in the Early Republic

- Treaty of Fort Stanwix: In 1784, under the Articles of Confederation, the government tried to solve the problem of native land claims north of the Ohio River by working out the Treaty of Fort Stanwix. The negotiations occurred with the six-nation Iroquois Confederacy. The stated purpose of the negotiations was to formulate a peace treaty in the wake of the Revolution (in which two of the six Iroquois nations had sided with the British).

- Battle of Fallen Timbers: At the Battle of Fallen Timbers (1794), the Indians were soundly defeated by superior American firepower. The following year, 1795, native groups gave up claims to most of Ohio in the Treaty of Greenville. The treaty brought only a temporary peace.

- Cotton Gin: In the decades after the American Revolution, slavery became increasingly important in the South. Eli Whitney’s invention of the cotton gin in 1793 set the stage for a remarkable growth in the production of cotton, in the growth of the southern economy, and in the reliance on slavery

AP Biology Resources

- About the AP Biology Exam

- Top AP Biology Exam Strategies

- Top 5 Study Topics and Tips for the AP Biology Exam

- AP Biology Short Free-Response Questions

- AP Biology Long Free-Response Questions

AP Psychology Resources

- What’s Tested on the AP Psychology Exam?

- Top 5 Study Tips for the AP Psychology Exam

- AP Psychology Key Terms

- Top AP Psychology Exam Multiple-Choice Question Tips

- Top AP Psychology Exam Free Response Questions Tips

- AP Psychology Sample Free Response Question

AP English Language and Composition Resources

- What’s Tested on the AP English Language and Composition Exam?

- Top 5 Tips for the AP English Language and Composition Exam

- Top Reading Techniques for the AP English Language and Composition Exam

- How to Answer the AP English Language and Composition Essay Questions

- AP English Language and Composition Exam Sample Essay Questions

- AP English Language and Composition Exam Multiple-Choice Questions